Gates open and the procession begins. Thousands line the street, throwing flowers and laurels, waving madly, reaching to touch power as it passes them. Security guards watch the crowd for dissidents, agitators, and zealots, intent on doing harm. The man coming through the gate sits tall in the saddle, looking every bit the champion he is meant to be. A mantle of authority rests easily on his shoulders as he climbs higher to the center of the city, taking his rightful place as lord protector of this people.

While this sounds like a political rally from our prolonged and protracted presidential season, the parade I describe took place two thousand years ago in Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. No – not that parade – not Jesus’ triumphal entry. The other one – the triumphal entry of Pontius Pilate into Jerusalem.

What? You don’t remember Pilate’s parade? Well, it’s no wonder. Pontius Pilate’s grand procession into Jerusalem has been left to antiquity in dusty tomes and ancient scrolls, for no one to remember, save a few ardent historians. Fortunately, two of those ardent historians, John Dominic Crossen and Marcus Borg, wrote a not-so-dusty tome describing the historical and political context for the final chapter of Jesus’ ministry on earth. Their book, Last Week, is a fascinating look at the world Jesus was trying to change. They begin as we begin this Holy Week, with Palm Sunday, and the two triumphal entries that paraded through Jerusalem that day.

Our story begins with Passover, the high-holy day for the Jewish people. Jesus and his disciples make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, along with hundreds of thousands of other faithful Jews, to offer their Passover sacrifices at the Temple. In First Century Jerusalem, the Temple was the center of the Jewish faith, the place where the High Priest interceded with God on behalf of God’s people, where sins were forgiven. It was a source of national identity and pride, rebuilt in splendor by Herod the Great. It was the envy of all the nations.

Pontius Pilate also came to Jerusalem for Passover, but not to atone for his sins. Pilate didn’t live in Jerusalem. It was too insular and partisan, hostile toward Gentiles, especially Romans. Like other governors, Pilate lived in the beautiful seaside town of Caesarea by the Sea, also built by Herod the Great. But as appointed governor of Judea, he was tasked with keeping the peace, especially during holy days, when emotions ran high and the subjugated citizens of Jerusalem burned with revolutionary zeal to overthrow their Roman oppressors. His title and his life depended on maintaining order in the Empire, particularly during Passover, the festival celebrating Israel’s freedom from the bonds of Egyptian slavery. So Pilate made the sixty-mile journey to Jerusalem, accompanied by hundreds of Roman troops, to remind the Jews that they may be God’s people, but Rome was still their master.

Traditionally, Pilate paraded into Jerusalem on the first day of Passover Week, entering the west gate – the front gate – with legions of chariots, horses, and foot soldiers, dressed for battle and armed with swords and spears. Rome’s authority would not be questioned. The majesty with which Pilate enters the front door of the city was meant to inspire awe and fear, respect and obedience.

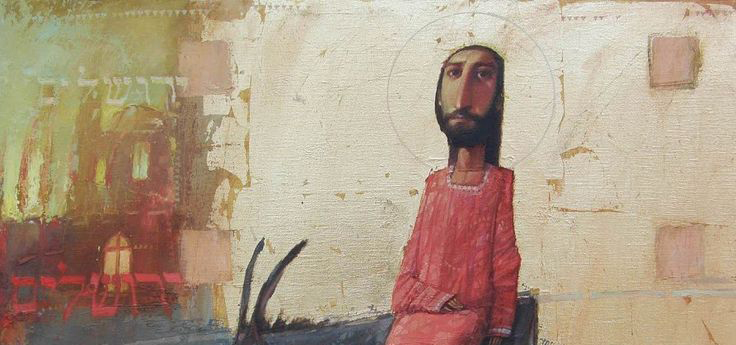

Meanwhile, at the east gate – the back gate – another parade is underway. This parade was just as carefully staged as Pilate’s entry into Jerusalem. It was a counter-procession, a different vision of what a Kingdom should be, a subversive action against the powers that ruled Jerusalem. Jesus’ humble, yet triumphal, entry into Jerusalem stood in contrast to the magnificence and brutality on display at the opposite end of the city. Jesus brings peace, while Pilate brings a sword.

Jesus’ entrance was planned this way. Two disciples slip into Jerusalem to secure a colt from its owners, who know they are coming. They even have a pre-arranged password: “The Lord needs it.” Literally, the Greek says for the disciples to tell the colt’s owners that the colt’s owner needs it. The words make no sense unless we understand that Jesus’ triumphal entry was designed to rival that of Pilate’s.

They planned it to be a royal entrance. Jesus riding a colt into Jerusalem reflected the Messianic prophesy of Zechariah: “Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey; on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” Those watching the back-door procession knew Zechariah and the prophesy. Jesus’ entry was a symbol of salvation – the return of God’s king to God’s people.

A large number of Jesus’ followers, a “multitude of disciples” it says, shout loudly, for everyone to hear, “Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest heaven!” This is dangerous language. It’s inflammatory. It’s treason. The entire spectacle from riding a colt, to spreading the cloaks, to proclaiming Jesus as king is sedition.

The Jewish religious leaders are the first to try to stop it. You would think that with Rome’s religion in direct conflict with Judaism, the Pharisees and priests would welcome Jesus as the one to free them from Roman rule. But you see, the Temple and all those who served it were in Rome’s back pocket. Rome did not force their religion on the Jews, as they did with other conquered territories, because the Romans considered Judaism an ancient religion. Jews were allowed, by the beneficence of the emperor, to practice a different faith, so long as Roman order was maintained and the Roman tribute was paid. Should anything troublesome happen, Rome would come down hard on the Temple – and it does fifty years later.

Herod the Great, builder of the Temple, appointed king of Judea, set up the Temple leaders, including the High Priest, then limited their power. He granted them land and wealth, in direct violation of Mosaic law. Priest weren’t supposed to own land. They corrupted the system, twisting the law to their own advantage. Those who ruled the Temple, and those who worked for them, were the one percent, and they worked closely with Rome in a delicate balance to keep the citizenry compliant while maintaining their own wealth and power.

I want to be clear: these weren’t bad people. They were good parents and loyal citizens. They were faithful wives and husbands. They participated in their community – went to weddings and funerals, generously offered help and advice, owned businesses and provided jobs. They accepted their position as a given. They weren’t evil, but a part of a corrupt system that perpetuated itself. They considered their life and the lives of those not as fortunate as them, well, just the way things were.

Then here comes the Messiah through the back gate on a donkey to ruin it all.

That was the plan, after all. But, as Robert Burns said, “The best laid plans of mice and men are often gone awry.” As we plunge into Holy Week, we witness Jesus’ triumphal entry turn into the Via Dolorosa, and hear the shouts of “Blessed is the King” become cries of “Crucify him!” Standing against the powers of this world is a good way to get killed. The disciples may not have expected the outcome of this week to be a cross, but there is some hint that Jesus did. As he approached the city, sitting on that donkey, listening to the adulation, Jesus was crying over Jerusalem. He knew the crowd did not recognize what passed before them; and he knew the fragile relationship they kept with Rome would ultimately crush them all.

Still he came. Still he stood. And still he sacrificed himself for peace.

Hear the fullness of Zechariah’s prophesy:

Lo, your king comes to you;

triumphant and victorious is he,

humble and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim

and the warhorse from Jerusalem;

and the battle-bow shall be cut off,

and he shall command peace to the nations;

his dominion shall be from sea to sea,

and from the River to the ends of the earth.

Angels proclaimed at Jesus’ birth: “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace and good will among people.” Jesus’ disciples echoed the angels’ song: “Peace in heaven and glory in the highest heaven!” The multitude proclaiming Jesus as king wasn’t made up of the Temple elite. The disciples at the back gate, hailing Jesus as Messiah, calling for peace on heaven and earth were the blind and the crippled, the poor and the despised. They were everyone from the previous chapters who were healed and loved and accepted: the tax collectors, the beggars, the ten lepers, the man with the unclean spirit, the paralytic, Jarius and his daughter, the widow and her son, the centurion and his servant, the woman with issue of blood, the woman with the alabaster jar, and all the little children. They proclaimed the One who comes in peace, for peace.

Though it’s two thousand years later, we aren’t that far away from Jerusalem on that Palm Sunday. Nations continue to kill their own people in order to maintain power. Refugees crowd into filthy camps because no one will take them in. Governments allow police brutality, mass incarceration, and poisonous water into impoverished communities because the poor cannot fight back. Banks and corporations have free reign to destroy our environment and gamble with our economy because wealth and power are synonymous. Is it just the way it is? Who will stand for them? Who will stand for us?

I was reminded last week that being called of God doesn’t wield the star-power you’d think it does. You don’t get parades or accolades or even a living wage. You get the back gate, the grateful support of a few, and a lot of angry folks who don’t want change. God is not kind to God’s prophets. More often than not, they end up on the wrong end of a rope. So it comes as no surprise that God’s Son ends up on a tree by Friday – all because he stood for peace.

We can feel sad for the poor and send money to the sick, we can worry for the homeless and the country-less, we can even Tweet our support for social programs and race relations. But at some point we have to stand against the front-gate parade without the benefit of swords or armor. We are called to be disciples, standing for what Jesus stands for – welcoming the stranger, healing the sick, making people whole again – even the ones we don’t like, even the ones who scare us. This is shalom. This is peace – whose only path is through the back gate and on to the cross.

Fortunately, it is also the path to resurrection.

Thanks be to God.

(Sermon preached on Palm Sunday, 2016 at the Hermitage, scripture: Luke 19:28-40 & Psalms 118)

[…] year, I had the privilege of preaching to you on Palm Sunday. I don’t expect you to remember the sermon – so breathe easy, there won’t be a quiz. Last year we looked at the Gospel of Luke; today, […]

[…] In through the Back Door […]

Excellent. Came upon this sermon of yours as I was searching for a reference to Marcus Borg’s writings on the Palm Sunday counter-procession. Thank you for making what Borg offers even more helpful as I prepare to share a word with our folks here in Ipswich, MA this Palm Sunday.

Thank you for reaching out, Brad! And for reading – have a blessed Easter and Holy Week! Stay well!

I just wanted to say I came across this while writing a Palm Sunday/Passion Sunday sermon and it is exactly what I was trying to write. The whole thing resonated with me and gave clarity to the message God was stirring within. I don’t know you, but thank you for your work here.

Thank you, Jeremy! Have a blessed Holy Week – and stay well!

Thank you, for helping me put thoughts into words.

My husband and I are PCUSA MoW&S. I read him your sermon while he was driving because it sounds like his sermon for this Sunday. I told him your sermon sounded like a Scot (like me) wrote it. We both loved it, so we read your bio. He said, “Boy, she sounds like you!” I said, “I know.” I was a filmmaker before seminary, and I’m often accused of blethering.

Thank you, Lesley! I’m so glad you found the sermon meaningful. And yes – there’s a lot of Scot in me (and a healthy bit of Irish and English so that I’ll never be able to tan, LOL.) It’s wonderful to hear that there are other creatives out there with so much good to say. Sending blessings!